|

Sahm Tell Political polarization is not a new phenomenon in the Middle East, but in Jordan, the landscape has grown increasingly fragmented in recent years. The war on Palestine, particularly the recurrent hostilities in Gaza and the West Bank after October 7th, has profoundly influenced Jordan’s domestic politics and sociological tapestry, exacerbating existing divisions and creating deeper fault lines.

Bertille Lietar On October 8, when Hezbollah opened a front in South Lebanon to support Hamas against Israel, it plunged a politically paralyzed country into an unpredictable dynamic, pushing the issue of the presidential vacuum into the background. Left without a President since October 2022 and without a fully-fledged Government, the Lebanese state finds itself limited in controlling the extent of a conflict it is unwilling to entertain.

Yeghia Tashjian On February 13-14, 2024, I received an invitation to attend the 13th Middle East Conference of the Valdai Discussion Club and the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow. The conference, titled “Time for Decisive Action: A Comprehensive Settlement for the Sake of Stability in the Region,” assembled more than 50 participants from 16 countries, mainly from Russia, Turkey, Iran, and Arab countries. Notable figures at the event included Russia’s Foreign Minister, Sergei Lavrov, who delivered a speech, and Mikhail Bogdanov, the Deputy Foreign Minister and Special Presidential Representative on the Middle East.

The event was important in assessing the post-October 7 developments in the region and analyzing how Russia is positioned in this challenging environment. The conference was divided into six sessions: “Towards a Comprehensive Settlement in the Middle East,” “Heritage of Colonial Policy and Its Echoes in the Middle East,” “Question of Palestine – What Is Next?,” “Diversity of Actors in the Middle East: Is Balance Achievable?,” “Is a Nuclear-free Middle East Possible?,” and finally, “Economic Cooperation in the Region: Opportunities and Challenges.” During the last session, I discussed the economic corridors, interconnectivity, and bilateral ties between Russia and main regional actors. In addition to addressing the escalation in Gaza and the Palestinian Question, the conference explored the dynamics of Russian-Turkish relations, Iran’s motives in the region, and the rise of non-state actors. It was mentioned that positive interaction with Turkey is crucial for Moscow to address its objectives in the region. In this regard, Taha Ozhan, the Research Director of Ankara Institute, and Pavel Shlykov from the Department of History of the Near and Middle East at the Lomonosov Moscow State University reflected on the complex relationship between Turkey and Russia, later published into papers. Ozhan and Shlykov argue that a personal dynamic shapes the relationship between the two countries, citing personal interactions between Presidents Putin and Erdogan. They emphasize that the flexibility and compartmentalization of conflicts are facilitating strong and smooth progress in developing bilateral ties. Ozhan argued that Turkey is finding itself in a geographically challenging region affected by international geopolitical polarization and regional tensions. Consequently, managing security risks is becoming imperative for Turkey and its “exceptional relationship with Russia has allowed it to preserve both its interests and relations with Moscow since the early days of the war.” Shlykov stated that Turkey, a NATO member and once pro-Western country, is now positioning itself as an independent and proactive player in the region, engaging in “strategic hedging.” The Russian expert mentioned that Turkey’s mediation activities, mainly related to Ukraine, have served Russian interests and elevated Turkey’s standing in the region. However, despite all the pragmatism and foresight of Turkey’s diplomatic tactics in the Middle East, there are still some limitations preventing Turkey from determining the regional order. Shlykov concluded that Turkey is becoming another player that amplifies multipolarity in the Middle East. Iran is another important player in the region, collaborating with key partners and non-state actors such as Hezbollah and pro-Iran Iraqi militias. Iran’s objective is to expel US troops from Iraq and Syria. While this would not be an easy task for Iran, the growing pressure on the US and intensified attacks on its military bases in these countries may impact the views and positions of the main US presidential candidates this Autumn. Former President and primary Republican presidential candidate, Donald Trump, hinted at his intention to withdraw US troops from North-Eastern Syria, thus exposing the vulnerability of the Kurds and placing them at the mercy of Ankara, Moscow, Tehran, and Damascus. In his speech, Lavrov also hinted that the “Americans will not stay there forever.” Having control over North-Eastern Syria, Russia would strengthen its position over regional stakeholders active in Syria and gain access to the energy resources located in the region. The escalation in Gaza also raised the importance of regional non-state actors such as Hamas, Hezbollah, Houthis, and others for Russia. These non-state actors are now asserting themselves through either proxy or direct wars, challenging the Western-imposed regional order in the Middle East. It is not surprising that the conference was preceded by a report paper presented by the Valdai Club titled “Gaza. Yemen. Epicenters of Pain. Feelings, Myths and Memory in the Middle East,” which studies the identity-making and mobilization of the above-mentioned non-state actors in the region. The war in Ukraine has pushed Russia to seek new partners in the region and actively engage with them in reshaping regional politics. The war in Gaza is a golden opportunity for Russia to engage with Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Jordan in addressing a comprehensive peace deal to the Palestinian question. Hence, by bringing the policies of these countries closer, Russia aims to consolidate its diplomatic posture in the region and form a united front to pressure the US into addressing the two-state solution. For this purpose, from February 29 to March 2, intra-Palestinian meetings and talks were held in Moscow under the Russian government’s auspices. Hamas, Islamic Jihad, Fateh, and around ten other Palestinian organizations participated in these consolation meetings. According to Bogdanov “Moscow’s goal is to help various Palestinian forces agree to unite their ranks politically.” By hosting these meetings, Russia is promoting itself as a defender of the Palestinian cause, thus sending a strong positive message to the wider Arab and Islamic world. Meanwhile, Moscow continues to positively engage with Hamas, viewing it as a key non-state regional actor that Russia must deal with to assert greater influence in the Middle East. Understanding these developments, Russia’s increasing economic and political interaction and involvement in the Middle East will further enhance cooperation between Moscow, Ankara, Tehran, and the Gulf countries. As each of these actors individually lacks the capability to shape regional security, despite their differences, they can compartmentalize these differences and act together in shaping the multipolar regional system. If according to Russia, the war in Ukraine has enhanced the transition of the global system to a multipolar world order and has given additional space for the “World Majority” (non-Western states), the war in Gaza has tarnished the image of the West in the region and pushed regional actors to deepen their cooperation with other global actors, such as Russia and China, to reshape the new regional security architecture. About the Author Yeghia Tashjian is International Affairs Cluster Coordinator at IFI. Nizar Bou Karroum The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013, has significantly expanded China's economic and political influence in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. The initiative, which consists of a new Silk Road Economic Belt and a maritime road, has drawn in 147 countries by 2023, primarily low and middle-income countries [1]. China signed agreements with 21 MENA countries, including 18 Arab countries, on joint projects for the BRI. By 2023, Middle Eastern countries received 23% of BRI engagement, aiming to further increase their cooperation with China [2].

China's relationship with MENA countries dates back to the Cold War era, with the Non-Aligned Movement attracting many countries seeking neutrality. However, relations remained limited, especially during the Maoist era. China's economic reforms led to adjustments in foreign policy, focusing on fostering improved relations with MENA countries to secure stable oil supplies [3]. Despite these efforts, trade and economic exchanges with the Middle East have only made limited progress reaching USD 1.7 billion in 1985 [4]. In the 2000s, Sino-Middle Eastern trade relations reached new highs, as China viewed the region as an attractive market and a suitable source for oil imports. In 2001, the Communist Party of China adopted the strategy of "going out" prompting Chinese private and public actors to invest in the Middle East [5]. The period leading up to Xi Jinping's 2013 takeover saw a further increase in Chinese trade relations and political and armed presence. The launch of the BRI marked a new era of cooperation between China and the MENA region, evident in enhanced ties with MENA countries. Over the past few years, China concluded comprehensive strategic partnerships with a number of MENA countries including Algeria, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Iran, and Egypt. Comprehensive strategic partnerships, according to Fulton [6], occupy the highest tier in the hierarchy of Chinese partnerships and prioritize “full pursuit of cooperation and development on regional and international affairs.”

China's BRI has faced criticism regarding its financing policy targets and large-scale infrastructure projects without sufficient financial viability. China's loans have higher interest rates and shorter repayment windows than loans from other creditors, making it an alternative lender of last resort. The BRI has also led to concerns about China's influence and motives in the region, as some countries have grown heavily indebted to China as a result [3]. Despite China providing significant debt relief and restructuring to these countries, examples like its acquisition of the Sri Lankan Hambantota Port through a 2017 debt-for-equity swap continue to raise concerns about China's influence and motives. The BRI has further been accused of lack of transparency, with Chinese lenders criticized for corruption and manipulating partner countries [9]. Critics point at the projects’ murky nature and the insufficient disclosure of information, raising questions about China's intentions. Finally, China has been criticized for contributing to environmental damage around the world by exporting its most environmentally unfriendly technology through the BRI [10]. The introduction of BRI projects to the MENA region brought about promising opportunities for development in partnering countries. Chinese investments in energy, infrastructure, technology and security have the potential to catalyze growth in MENA countries, addressing pressing needs for progress in their economies. However, increasing global concerns surrounding BRI projects and lessons learned from previous MENA experiences underscore the need for the region’s countries to adopt preemptive measures. These measures are essential to ensure optimal outcomes and success from such projects, including:

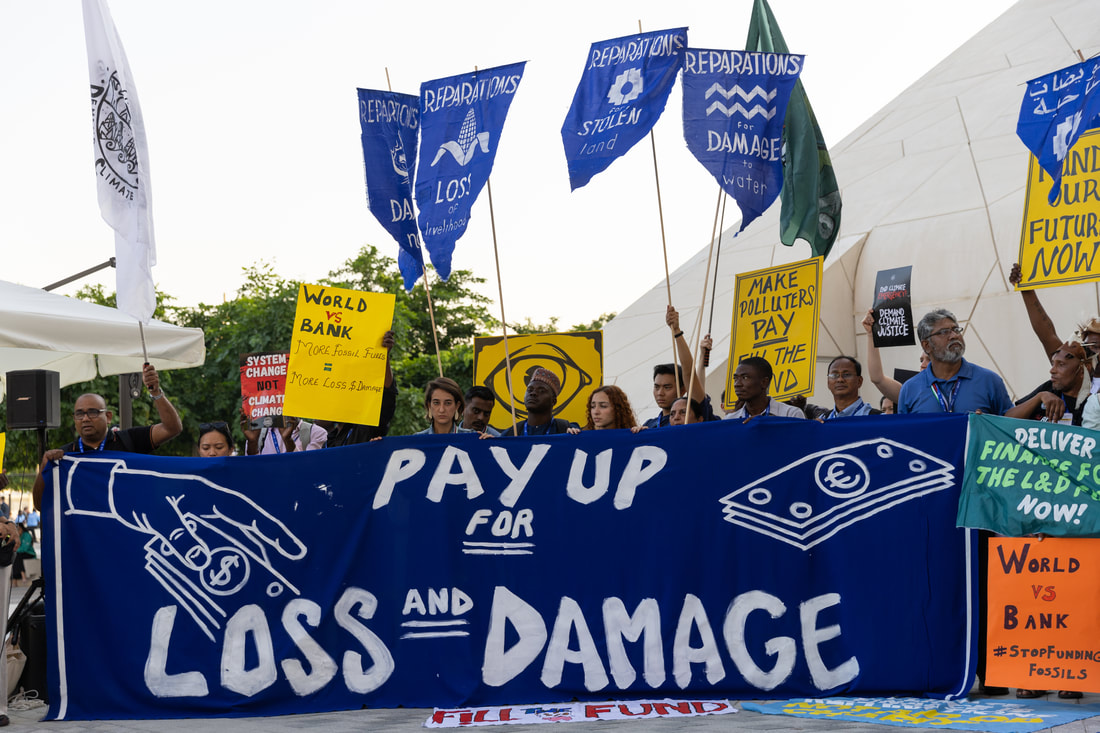

About the Author Nizar Bou Karroum is currently an intern at IFI, within the Economy and Finance Cluster. COP28 Sees Compromises on Loss and Damage Demands in the Absence of Accountability for Big Polluters12/8/2023

Rami Abi Ammar Established at last year’s COP27, the loss and damage fund became a central item on the agenda for negotiations at this year's United Nations Climate Conference, COP28, held in Dubai. The fund has been a tabled demand since 1991, as developing countries bearing the climatic brunt of historical emissions and continuing extraction activities by developed industrialized states seek finance for averting, minimizing, and addressing climate disasters. Since its recognition in Article 8 of the Paris Agreement, loss and damage became a third pillar of international climate policy, along with mitigation and adaptation. However, since its recognition and later establishment, the fund has not received any designated financing or any operational structure.

On only its first day, COP28 host country, UAE, announced a USD 100 million pledge to the loss and damage startup fund, matched by Germany and followed by USD 145 million pledge from the rest of the EU, USD 75 million from the UK, USD 24.5 million from the United States, and USD 10 million from Japan. The kick-off of negotiations around the loss and damage fund and the initial, first-day commitments standing at USD 429 million have been lauded as a “landmark deal.” In the days ahead of this announcement additional contributions from France, Italy, Ireland, Norway, Canada, and Slovenia have raised the total commitments to USD 700 million (as of December 6, 2023). Yet many questions still arise regarding the operationalization of the fund, financial commitments to it, and the eligibility of developing countries to access it. As it stands, the recommendations and commitments to the fund meet few of the demands set out by developing countries over the course of 30 years. The draft decision outlining recommendations on the operationalization of the fund appears to be strewn with compromises answering to the interests and trepidations of developed countries. Initial pledges are only a fraction of the USD 100 billion/year by 2030 proposed by developing-country members of the Transitional Committee in a submission to the Conference in September. In their submission, the members emphasized that this figure is “not meant as a ceiling, but rather as a minimum commitment,” with the potential to scale up given the rising trajectory of losses and damages under current climate realities. This is in light of a growing evidence base suggesting costs of climate-related losses and damages could be as high as USD 680 billion annually, taking into account ‘residual’ damages. Attempts at describing a funding scale or minimum commitment into the final recommendations for the operationalization of the fund have been met with rejection and thus left out of the draft decision. US Transitional Committee member Christina Chan rejected the mention of any figure describing the scale of the fund in the committee’s final recommendation documents last October, deeming it out of the mandate of the committee. More critically, the language in the draft decision excludes liability and compensation for loss and damage, highlighting instead that the funding arrangements, and the fund itself, are based on “cooperation and facilitation.” Thereby, paying into the fund remains voluntary and parties are not required to fulfill any financial commitments, even if they are pledged. This has long been a point of contention between developing countries and large industrialized polluters including the US, Europe, China, and the Gulf petrostates. For the US particularly, any pathway towards an outcome on the fund has become contingent on the exclusion of liability and compensation language from decisions, as pushed by US Transitional Committee member Chan in the fifth meeting of the committee in early November. This can be seen as a clear safeguard for the US against any legal accountability for its historically high emissions. Concessions on the modality of the fund are seen not only in voluntary contributions, but also in the recommendation of what has been dubbed “innovative” finance mechanisms that remain within the realm of small grants and highly concessional loans. Other recommendations include “direct budget support and policy-based finance, equity, insurance mechanisms, risk sharing mechanisms, pre-arranged finance, and performance-based programs” all of which fall short of providing sustainable and independent revenue streams for the fund, particularly those from proposed bunker fuel and airline fuel taxes. Developing countries have repeatedly called for reparatory and solidarity-based financing to address losses and damages, but they continue to be met with concessional loans and private sector financing in attempts to cower away from the polluter-pays principles. Another concession to the US came with the appointment of the World Bank as the interim operator of the fund in the final recommendations to COP28, further highlighting the reliance of the fund on the modality of multilateral development banks. The loss and damage fund was envisioned to be an independent, standalone entity operating under the architecture and financial mechanisms of the UNFCCC. Its extension to the World Bank, whose president is appointed directly by the US and whose board is predominantly inclined to represent the interests of developed countries, has raised concerns of observers regarding the influence of big polluters over the fund in light of the Bank’s questionable environmental credentials and lack of transparency. The World Bank has less than a shining history in the developing world, particularly with the struggle of its concessional lending arm - the International Development Association (IDA)- to replenish financing for lenders already impacted by its shortfalls. The World Bank’s expansion into the climate space has also come into question when it has invested over USD 14.8 billion into fossil fuel projects and policies since the Paris Agreement and USD 3.7 billion in oil and gas trade finance in 2022 alone. The appointment of the World Bank remains temporary, with the draft decision granting it six months after the conclusion of COP28 to confirm its commitment and finalize its program. However, the permanent appointment of the World Bank is not far-fetched and would render access to loss and damage funding yet another lengthy, complicated process out of reach of developing countries reeling from disaster. Notably, developing nations requiring loss and damage financing are also faced with unfolding public debt crises, and their eligibility could be undermined by limited lending capacities. At the heart of demands for trigger-based solidarity funding is the difficulty faced by countries with limited means, especially in the wake of climate-induced events, to quantify, justify, and properly attribute losses and damages. Stringent criteria and complex applications for small grants and loans, typical of World Bank and other climate funds, already disadvantage parties that are unable to provide timely, cohesive, accurate, and multi-scalar datasets to prove eligibility. The increasing lure and role of attribution science used to link extreme weather events with anthropogenic climate change can create geographic bias against states and regions with data limitations. More importantly, attribution frameworks can occlude or misrepresent critical historical, social, and political-economic factors that lead to socio-ecological conditions and relations that produce and reproduce vulnerability to climate change losses and damages. They also present a problem for recovery of non-economic losses including displacement and impacts on human lives, mobility, and cultural heritage. Attribution science, therefore, should not be a formal requirement to access loss and damage financing. It may not even be in favor of the interests of industrialized nations when attribution frameworks pick up on their culpability in constructing both the environmental and socio-political conditions for disaster. Even then, what science are big polluters willing to accept? When COP28 President and ADNOC CEO Sultan Al Jaber claims there is no science behind demands at phasing out of fossil fuels, it brings into question whether negotiations at COP are set up to fail. Who is at the table at COP28? Can the demands of developing countries for accountability be heard over the record number of fossil fuel lobbyists in attendance at this year's conference? The USD 700 million in pledges to loss and damage combined with UAE’s USD 30 billion private climate finance fund and other pledges towards climate-related projects remain dwarfed by an overall USD 7 trillion in subsidies to the fossil fuel industry by many of the donors at COP28. Attitudes on phasing out fossil fuels remain cautious, as oil producers and investors seek to dilute and obscure language within agreements. COP28 cannot be removed from the current graver and wider socio-political context, and depoliticizing climate negotiations is harmful for communities suffering from its repercussions. The summit continues amid gross human rights violations and indiscriminate environmental crimes in the region which it fails to address. Israel’s brutal aggression on Gaza, amounting to genocide, ethnic cleansing, and deliberate destruction of water, food, and energy infrastructure is supported by direct US military aid of USD 14.5 billion. That is over 600 times the amount the US has pledged for the loss and damage fund - a fraction of the USD 3.8 billion per year in US military assistance to Israel since 2016. Furthermore, environmental damages and emissions from growing military aggression cannot be dismissed or overlooked. This is especially critical when military aggression continues to be used to support the extraction of natural resources, such as in the case of ongoing displacement and violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Just climate action should come hand in hand with supporting human rights. Without addressing prevailing power structures, COP will continue to fail as an avenue for accountability and restitution for the human, economic, and physical losses of global anthropogenic climate change. About the Author Rami Abi Ammar is a Climate Change and Environment Researcher at IFI. Mira Machmouchi Food security has become an issue of international concern due to the ongoing geopolitical turmoil and magnifying impacts of a changing climate. Since 2011, food subsidies in the face of food insecurity in the MENA region cost up to $21.6 billion and were the highest in Iraq, Syria, and Egypt amounting to over 2% of their GDP [1]. The United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), defines food security as the situation in which “all people at all times have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life” [2]. Globally, the 2023 Global Report on Food Crises found that 258 million people are impacted by crisis or acute food insecurity [3]. While the world tried to recover from COVID-19, it was hit with energy and food insecurities generated by the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. The ongoing conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region directly impact the food security of affected states and their neighbours. This situation is increasingly complicated by a multitude of political factors and aims. The Russian invasion of Ukraine caused a general increase in food insecurity in the MENA [4]. Russia and Ukraine accounted for more than one-quarter of global wheat exports and the most vulnerable to the impact were states prone to the war-induced price hikes; these included Lebanon, Egypt, Libya, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Tunisia, Iran, Jordan, and Morocco [5]. The average inflation of food rose in almost all MENA economies with the most notable increases in Egypt, Morocco, and Algeria [4]. The spiraling food costs and the supply disruption risks have been particularly challenging for countries importing wheat from Russia and Ukraine [4]. The MENA region’s food security was severely implicated by the war. Egypt is one of the countries most impacted since it imports over 60% of the wheat consumption across a country with a population exceeding 110 million. Likewise, the rise of staple food costs impacted over half of Yemen’s population with around 5.6 million people experiencing emergency levels of food insecurity. Lebanon also experienced a strain on its wheat sources as it imported approximately 75% of its wheat imports from Russia and Ukraine [5]. Both Lebanon and Jordan were largely dependent on this wheat import source while simultaneously bearing the additional strain of an influx of Syrian refugees and a surge in their respective populations [1]. These struggles have added to the dire impacts of the chronic political and military tensions afflicting the MENA region [4]. Climate change remains a top driver of the expanding humanitarian needs and suffering with the increasing hunger and water crises. Simultaneously, the food system is one of the top drivers of climate change, contributing to a third of global greenhouse gas emissions and consuming up to 30% of the world’s total energy demand, which mostly comprises fossil fuels [3]. Two main drivers affect food security globally. Along with global conflict, extreme weather events due to climate change have led to world hunger [3]. The MENA region has witnessed worsened increasing extreme weather patterns over the past decade, including situations of increased heat waves, droughts, floods, cyclones, and wildfires leading to difficult local farming [6]. Out of the 17 most water-stressed countries in the world, the MENA region is home to 11 of them. Compared to 70% of water going to agriculture worldwide, the region’s agricultural sector utilizes up to 80% of its water supply. This greatly limits the region’s ability to diversify its water supply use due to channeling the bulk towards agriculture [6]. Concurrent with increasing water scarcity and a lack of sufficient arable lands, domestic food production is at risk. These environmental stresses put domestic agriculture at risk due to the lack of innovation levels and resources needed to be combatted. Most MENA countries focus on agricultural strategies that promote exporting profitable crops, which require large amounts of water and arable land while importing staple foods. These issues are further amplified by the lack of stable infrastructure, rural development, and policy consistency [6]. Locally, social stigmas associated with agricultural work and lower earnings expectations for small-scale farmers also demotivate local efforts for domestic production. Collectively, these factors, amongst others, have led to the highest urbanization rates in the world with high rural-urban migration and farmer displacement rates [7]. The MENA region also experiences one of the highest rates of population growth worldwide. Food demand rates increase accordingly while resources are depleted, and future production prospects remain neglected. High temperatures are leading to heightened demand for increasingly scarce resources such as water. The region has suffered from spatial and temporal extents of pest infestations in addition to an increase in extreme events such as dust storms, droughts, and floods. These are all factors that have led to an overall increase in the cost of agricultural production. Adaptation to such scenarios witnessed in the MENA region, with a particular increase of above 2 degrees Celsius in average global temperatures, becomes increasingly difficult and more expensive [6]. To combat the high cost of food and food production, some MENA countries implemented subsidies to offset the burden on citizens [6]. Subsidies continue to burden already weak economies and eventually become unsustainable, leading to social upheavals [6]. Further, deteriorating agricultural production has caused a rise in local and cross-border migration adding to the stress of governments and host communities. In 2023, this was evident in at least five countries in the region that have witnessed food inflation of more than 60%. Lebanon and Syria both faced triple-digit food inflation of 138% and 105% respectively, while Iran, Turkey, and Egypt experienced annual food inflation of more than 61%, causing populations to experience difficulty in affording essential food items such as bread, rice, and vegetables [8]. Globally, food prices remain at a 10-year high even with the slight global price decrease in recent months. By February of this year, 4 out of 15 countries in the region, Lebanon, Egypt, Syria, and Iran, were on WFP’s currency watch list due to depreciated currencies of between 45 to 71%. Over the past three years, the number of food-insecure people across the region increased by 20%, amounting to 41 million people since 2019 [8]. Different countries in the MENA region maintain different levels of food security statuses based on an array of factors. Gulf countries rank among the most food secure in the region with the United Arab Emirates ranking at 26 and Qatar at 29 globally out of 170 countries [6]. Despite lacking local production, their ability to purchase food imports on global markets is primarily derived from their substantial financial resources, largely stemming from their oil and gas revenues. On the other hand, Syria ranks at 148 while Yemen ranks at 160 in food security due to the ongoing turmoil in both countries; despite Syria’s previous status as the region’s breadbasket and its geographical location on the “fertile crescent” [6]. Syria and Iraq have also suffered from prolonged droughts and conflicts, which have decreased food production and reduced cultivation areas. The entire region has similarly fallen victim to prolonged droughts and heat waves, wildfires, flooding, erratic rainfall, and landslides [8]. These issues have festered into today’s worsening situation which has been repeatedly tackled with temporary solutions exacerbating the rising food prices and food insecurity. Concerns increase regarding the long-term implications of rising food prices and food insecurity in the MENA region. The strategic mitigation of food price inflation and food insecurity is at the forefront of MENA countries’ policy priorities. One main reason for the increased interventions by governments in food systems is their fear of rising food prices and insecurity fuelling social discontent. As the criticality of food insecurity persists in the region, governments and the international community must take action to address this issue. This begins with addressing the underlying causes of instability, conflict, and turmoil in the region. With skyrocketing humanitarian needs and increased societal struggle due to hunger and water scarcity, climate change remains the top driver. As one of the key pillars at the upcoming COP 28 in Dubai, sustainability is an essential component in creating resilient and adaptive solutions for locally-led initiatives focused on water and food. According to the COP 28 presidency, the region will be presented with “plans and opportunities in crisis settings to move from the provision of relief to climate-resilient development” [9]. The investment in advancing agricultural research and improving food production is necessary to utilize the diminishing resources available, optimize yields, and move forward toward a sustainable future. Food security remains a global issue and inter- and intra-regional cooperation today is vital like never before. In a vicious cycle of climate change, food insecurity, and increasing geopolitical tensions, COP 28’s presidency efforts in prioritizing food as a topic of discussion and focus are greatly encouraged. About the Author Mira Machmouchi is a Climate Change and Environment Researcher at IFI. Joe Boueiz On September 15, 2020, at an official ceremony hosted by President Donald Trump at the White House, the Abraham Accords were signed by Israeli Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu and the foreign ministers of the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed Al Nahyan and Abdullatif bin Rashid Al Zayani respectively. In the three years since the accords were signed, Israel and the UAE have deepened their ties in several areas such as trade, defense, technology, and energy. However, the outbreak of the conflict in the Gaza Strip, has put the UAE, and other signatories to the Abraham Accords, in an uncomfortable position. How will the UAE balance its profitable relationship with Israel amid the recent developments in Gaza? The origins for the UAE’s current foreign policy began with the outbreak of the 2011 Arab Spring when the UAE adopted a more muscular and interventionist foreign policy. It was one of the regional actors that called for the blockade of Qatar in 2017, supported anti-Assad groups in the early stages of the Syrian civil war, and has been the primary sponsor of the secessionist Southern Transitional Council group in Yemen. Over the last several years, its strategy has shifted towards using diplomacy and soft power to cultivate closer political and economic ties with other regional actors and establishing a regional order based on networks instead of alliances. The UAE has also adopted a more transactional attitude towards its neighbors, with a focus on mutual benefit. This differs from the previous approach held by Sheikh Mohammed Bin Zayed’s, or MBZ as he is popularly known, predecessors that prioritized stability above other factors. As one of the most influential politicians in the Middle East and a leading proponent of normalization with Israel, MBZ has been widely seen as the architect of the accords. In a speech at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, MBZ stated that the accords were “to send a clear message to the world and the region that we are striving for peace.” He also acknowledged that while the peace accord could be seen as a slight against the Palestinians, he justified signing the accords by stating that “every decision has risks, undoubtedly, and we live in a complex region. But the rewards are an incentive, and the outcomes we will achieve together are far greater than the drawbacks.” The operative phrase to remember in this comment is “rewards.” The economic benefits of the UAE’s recognition of Israel have certainly been substantial. As expressed in a 2023 research paper by Chatham House, “the synergies between the two countries across a broad range of sectors, including finance and investment, education, healthcare, technology, energy, agri-tech, food and water security” have allowed for a smoother economic integration between Israel and the UAE. In March 2023, the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), Israel’s first free trade agreement with the UAE came into effect, which eliminated tariffs on 96% of trade between the two countries, and is expected to increase bilateral trade from USD 1.2 billion to over USD 10 billion by 2030. The accords have also allowed for greater integration of the energy markets in the region. In September 2023, Israel’s energy minister, Israel Katz, met with the chief executive of Emirati energy firm Masdar to advance a tripartite deal between Israel, the UAE, and Jordan. Under the proposed agreement, two projects, Prosperity Blue and Prosperity Green, the UAE will fund the construction of a 600 MW solar plant in Jordan that will provide energy to Israel, and in return, Israel will export 200 million cubic meters of desalinated water per year to Jordan. These projects will help address Jordan’s water needs, while also expanding Israel’s clean energy network. The fundamental problem with the Accords, however, is that they were drafted to allow the normalization of relations between Israel and the Arab states by sidelining the Palestinians, since all previous attempts had been tied to the condition that any deal with Israel must be accompanied with a resolution to the Palestine Question. And while the UAE has criticized Israeli policies at times, some have expressed skepticism about the sincerity of the Emirati officials towards the Palestinians. With the recent escalation of the situation in the Gaza Strip, countries that have recognized the state of Israel, including the UAE, have been placed between a metaphorical rock and a hard place. When the current conflict first broke out, the UAE announced a USD20 million humanitarian aid package for the Palestinians, while also calling for an immediate ceasefire to the conflict and the protection of civilians. On October 16, it was reported that MBZ was in contact with Arab and non-Arab leaders to find a resolution to the conflict and called for all sides to abide by international humanitarian law. The fact that MBZ has been the only leader to reach out to Netanyahu to discuss the issue highlights just how precarious the situation has become for Arab leaders that have established relations with Israel. At the same time, the UAE has maintained diplomatic and economic ties with Israel by emphasizing that “we don't mix the economy and trade with politics”. Emirati political commentator Abdulkhaleq Abdullah succinctly described this political dynamic arguing that "Israeli politics are definitely difficult and there are a lot of ups and downs. But the Abraham Accord is a strategic decision, it will continue despite whatever goes on in Israel”. For the foreseeable future, it seems that the UAE is maintaining an observer position and waiting for the conflict to subside before it can start discussing diplomatic solutions with the Israelis and Palestinians. How long will the UAE be able to maintain such a position is unclear. While Emirati officials can hold out in the short term, the longer the conflict drags on and casualties mount, the harder it will become for the Emirati government to justify its overt relationship with Israel. While this does not mean that the UAE will reverse its recognition of Israel, it will have to rethink how it portrays this relationship to the rest of the Middle East moving forward. This could involve suspending projects with Israel, take a more proactive role in mediating the conflict, and even publicly denouncing Israeli actions in the Gaza Strip. It will also have to acknowledge that any further development of ties with Israel will not be able to proceed without incorporating the concerns of the Palestinians and the necessity of continuing to find a concrete path forward to a lasting resolution between the Palestinians and Israelis. About the Author

Joe Boueiz is currently an intern at IFI, within the International Affairs Cluster. The sudden, surprising and deadly attack launched by Hamas outside Gaza on the night of Oct. 7-8 may have shifted the Middle East as a whole into a dynamic that, in many respects, seemed to be moving away from lately. For more than two years, the region had been oscillating between tensions — some of them old, others new or renewed — and rapprochements — most of them transactional and cynical, but with a clear trend towards de-escalation, from Syria to Yemen, via the Iranian-Saudi detente.

What's happening today in Gaza can be described as a “breakthrough phenomenon.” A breakthrough and a tipping point too, perhaps, and undoubtedly a refocusing on a nagging issue that was drifting into oblivion: The issue of Palestine. As is often the case in these situations, the same question arises again and again: How confined or contained will this conflict remain, and when and where will the famous "unicity of theaters" we hear more and more about come into play? Of these, it is of course Lebanon that is emerging as the main candidate for the status of second front. The conflict between Hamas and Israel comes at a time when Lebanon is in the midst of a full-fledged socio-economic and political collapse, drifting towards a state of long-term chaos, a sort of enduring ungovernability with security institutions slowly melting. The system exploded, and nobody knows how long it will take for the country to recover. Given the speed at which the situation is evolving, one shouldn’t dare to venture into any bets as to whether a second front to the Hamas-Israel war will be opened in Lebanon. There have, and will be, some skirmishes on Lebanon’s southern border. However, these skirmishes are the language that Israel and Hezbollah know and use well but remain contained. I am “optimistic” of the fact that Lebanon will stay at bay, and for at least three reasons. The first one is technical. Hezbollah knows that given the situation in Lebanon, it would be extremely risky and costly to embark on a full escalation. The situation today is different from 2006, during the July Hezbollah-Israel war. Internally, Hezbollah doesn't have the domestic support it used to. The economic situation is disastrous, and Hezbollah couldn't take the burden of responsibility for completely destroying the country if a war were to break out. At the same time, Israel would be in a difficult place if it opens two or three fronts, noting that the Lebanese front is anything but easy. So it will not be a replica of 2006. Therefore, both parties have an interest in keeping the situation limited to the exchanges we’ve seen so far. The second reason relates to the energy equation in the East Mediterranean. Regardless of our opinion on the maritime delimitation and the gas exploration in the south, this is creating a strong deterrent to conflict. Both parties do not want to endanger what is now becoming physical infrastructure (including platforms in Qana and Karish) and no one is ready to take the risk of blowing this up. Hezbollah was very clear in the past months, saying that any conflict would involve the maritime installations of Israel in the South. It is doubtful that anyone would endanger this that easily. Finally, the third reason is geopolitical. If Hamas's actions in Gaza aim to torpedo or derail the rapprochement between Israel and the Gulf States by putting the Palestinian question on the table again – saying that if this isn’t addressed, nothing else can be done – then it is in the interest of the allies of Hamas, Hezbollah at the forefront, not to engage in the war. In other words, let Hamas and Palestine be at the center stage and not intervene. For all these reasons, it is fair to say that Lebanon will remain a side show, some minor fire and rocket exchanges notwithstanding, but it will remain limited overall. In the eventuality that Israel engages in a full offensive on Gaza, with the possibility of seeing Hamas be eradicated as a result. Att that point, Hezbollah and Iran would reassess their involvement. However, the automatism of opening a Lebanese front may well remain relative. Withs tensions heating up in the West Bank, a much more nebulous use of a platform for operations in southern Syria, actions by Iraqi groups against the American presence, the choices are now more open than before. For once, perhaps to Lebanon's advantage, it is this very "uniqueness of theaters", but also their multiplicity, which, paradoxically, could spare the country from being the only mailbox for the conflicts surrounding it. This was originally published as an Op-Ed in L'Orient Today on October 13, 2023, in English and French. Yeghia Tashjian This year’s BRICS summit in South Africa came amid a tumultuous, almost entropic period in global politics. Intensifying U.S.-Chinese competition and the war in Ukraine have emphasized geopolitical trendlines. Meanwhile, many newly formed “medium-powers” frustrated by U.S. global politics have found ways to raise their concerns and challenge the unipolar system by reducing their dependency on the U.S. Dollar, while increasing bilateral trade in their own currencies. For these countries, joining non-Western-led blocks such as BRICS has been the main objective.

Of course, BRICS may face particular internal challenges, while China and Russia have their own agenda against the West, and countries such as India, Brazil, and South Africa want warm relations and avoid sanctions. Meanwhile, the expansion of BRICS towards the Middle East will definitely have an impact on the shattered regional system. The Expansion of the BRICS and the Emergence of New Challenges Since 2022, BRICS has sought to expand its membership, as several developing and new rising powers expressed their interest in joining. During the 15th BRICS summit which took place in South Africa last August, the host President announced that six new emerging market economies (Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Iran, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Argentina) have been invited to join the group and full membership will take effect on January 1, 2024. According to many political analysts, the main objective behind this expansion is part of the plan to build a “multipolar” world system to increase the marginalized voices of the “Global South” in the world arena. With BRICS now counting 40% of the world’s population and a quarter of global GDP, by adding new members to the bloc, BRICS would be a stronger and more influential group, further advancing the concept of multipolarity. Despite divisions (mainly related to the worldview and the expansion of the bloc) among BRICS members, there is an emerging consensus that the current international order is unfair and, if not replaced, at least needs to be reformed. However, each member state has its own perspective on global affairs and the future of the bloc. Russia is keen on advancing this multipolar concept and sees BRICS’s expansion as a way to undermine the U.S. global order. After the war in Ukraine, Russia has looked to the Global South (mainly Africa and the Persian Gulf) to facilitate trade relations and bypass Western sanctions. Moreover, the presence of new members at the upcoming summit that will take place in Russia will give a positive international signal to Russia’s global standing. China also views the bloc as a tool to shape the global system and create an alternative order to the U.S.-led global order. China has been in favor of the expansion arguing that economic distress in some of the BRICS countries is weakening the bloc’s common identity, position, and enthusiasm to continue promoting the cooperation mechanism. As the era of the post-pandemic rapid economic growth in Brazil, South Africa, and Russia has passed, injecting fresh blood into the bloc would further accelerate economic activity within member states and around the globe. Initially, Brazil and India were not in favor of expansion, fearing that this would dilute their influence and impact their non-aligned foreign policies. Brazil, isolated from Eurasian political developments, does not have enough diplomatic weight as Russia or China in shaping global or continental affairs and believes that the expansion would diminish its influence as the leader of the Global South. Meanwhile, India, the most populated country in the world, is wary of the bloc becoming anti-Western in orientation and being used as a tool by China to increase its influence in Asia and the world. One of the founding nations of the non-aligned movement during the Cold War, India has carried this legacy even in today’s current great power competition. While it is also a member of the Chinese-Russian-led Shanghai Cooperation Organization, India’s political relations with the U.S. keep expanding, while working with Japan and Australia to counter China’s expansion in the Indo-Pacific. India has its also own interest in becoming a world economic power. While China’s economic engine may be sputtering at the moment, Bloomberg Economics predicts that India is ready to “pick up the slack and could boost the BRICS’ share of global GDP to more than 40% by 2040, compared with 32% last year.” How the Expansion will Impact the Middle East Four of the six countries invited to join are from the Middle East, suggesting a strong inclination to include the Middle Eastern states in the bloc. Nadeem Ahmad Moonakal from the Riyadh based-Rasanah International Institute for Iranian Studies argues that an expanded BRICS could have a considerable influence within energy markets as it would now encompass major oil-exporting countries as well as India and China, the world’s two largest oil importers. This will also push the Middle Eastern members to diversify their economic outreach, enter new markets, and open new funding opportunities in the region. Moreover, if BRICS members start trading energy resources with local currencies, there will be global implications for the energy market. Iran’s accession to the BRICS is a win for Russia, India, and even China. Moscow and Beijing have been trying to integrate Iran into their regional architectures. This was clear during Iran’s accession to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) in 2023, whereby Moscow and Beijing aimed to bring Iran within their orbit amid possible breakthroughs of nuclear negotiations between Iran and the West. For Moscow, Iran is an important partner in pushing its regional agenda in the Middle East (mainly Syria but also in Iraq and Lebanon). Hence, the recent China-brokered diplomatic rapprochement between Iran and Saudi Arabia was a diplomatic victory for Moscow and Beijing to minimize U.S. influence in the region. For Iran, this invitation is a new step toward strengthening its “Looking to the East” foreign policy. The Iranian leadership believes that the future international order will be centered on Eurasia and that the U.S.-led unipolar global order is in decline. Hence, by integrating into such blocs, Tehran sends a message to the West that it can confront U.S.-imposed isolation and is in no need of diplomatic engagement with the West over its nuclear program. Most importantly, Iran’s admission to BRICS, alongside its regional Arab rivals, UAE and KSA, can foster further de-escalation of tensions in the Persian Gulf, Yemen, and the Levant by providing these countries an additional venue for dialogue. Finally, Iran is the linkage of regional transit projects. The country has a geostrategic location bordering 13 countries and has strategic access to the Persian Gulf, Caspian Sea, Central Asia, and South Caucasus. In addition, it is part of China and India-backed international transit corridors. Already within this context, the General Director of the Railway Company in Iran announced on August 27 and for the first time in history, the transit of Russian cargo to Saudi Arabia through the Iranian section of the International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC) INSTC. For the Gulf states, the reasons for joining are slightly different. As China, Iran, and Russia may push for an anti-Western agenda, India, South Africa, and other future members may seek flexibility. According to Barak Seener, CEO of the geopolitical risk assessment group Strategic Intelligentia, Saudi Arabia “does not want to create an alternative to the dollar nor is attempting to undermine the post-World War II international order.” By joining the BRICS, the Arab monarchs of the Persian Gulf will “decrease their reliance on the U.S. and diversify their alliances while assuming a more important position of regional and global leadership,” but will not try to challenge the U.S. order. For the Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the logic of joining the BRICS has political and economic objectives. The eight-year conflict with Iranian-backed Houthis in neighboring Yemen was threatening oil facilities and distracting from his grand plan to turn the kingdom into an economic hub. Hence, ending this war through diplomatic means is a priority for the Kingdom. When it comes to the UAE’s interest, Nickolay Mladenov from the Washington Institute argues that by joining BRICS, the UAE will boost its geopolitical position and consolidate its relations with diverse actors such as India, China, Russia, and rising middle powers from Africa and Latin America. Final Thoughts The recent events – Chinese-brokered Saudi-Iranian deal and the expansion of BRICS to the Middle East – will bring China and the Middle Eastern countries closer. Some analysts argue that this is an effort by China to carve out more significant political influence in the MENA region, most notably by facilitating the Iranian-Saudi diplomatic agreement in March 2023 and the entry of several Middle Eastern members into the SCO (Iran as a full member in 2023 and the Gulf states and Egypt as dialogue members between 2022 and 2023). China’s outreach to the region fits into a broader Chinese coalition-building strategy among countries of the Global South, in part through its “Global Development and Global Security Initiatives,” through which it has articulated its vision for the future of the international order. Of course, Middle Eastern countries have many motivations to get closer to China. In addition to its economic attractiveness, there are certain geopolitical factors that come to play as well. For Iran, under the 25-year agreement signed in 2021, Tehran is eyeing for the USD 400 billion Chinese investment to turn the country into a regional transit hub connecting the Middle East to Eurasia. UAE and KSA, both OPEC members, expect China to remain a long-term growth market for oil as they are investing billions of dollars in Chinese oil refineries. Moreover, they view China as an attractive economic partner in achieving their objectives of economic diversification. Politically, and unlike the U.S., China has enough leverage to push Iran to engage with KSA on regional matters. Within this context, Turkey would be another strategic candidate in the far future to join the bloc, thus solidifying China’s position in the region. However, the direct political impact of BRICS expansion to the Middle East on the region is still far from a reality. Dr. Igor Matveev, Assistant Professor at MGIMO University, Valdai and Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC) expert, pointed out that it is too early to predict any concrete economic impact of the recent BRICS's extension to the Middle East and the Iran-Saudi relationship in particular. Nevertheless, Dr. Matveev stated that Saudi Arabia could contribute to the BRICS-affiliated New Development Bank by financing certain projects that could benefit the INSTC or develop joint projects with Iran under the BRICS political umbrella. In conclusion, the prospects for BRICS adapting to a new extended reality correlate with the ongoing transition from a unipolar to a multipolar world. This transition will have a direct impact on the regional system in the Middle East. The region is experiencing a transition as a result of the war in Ukraine, where traditional US allies are seeking to diversify their economic and political relations while pursuing an independent foreign policy with the aim to consolidate their position in the emerging global system. Ishac Diwan For their 15th annual meeting in South Africa, the main agenda item for the BRICS is their enlargement to new entrants – they now include five countries – Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. A popular joke goes by “nice bricks, but where is the mortar?” Perhaps that by growing, the group can get itself a better-defined agenda – in addition to a new name to replace an acronym put together by a British economist working at an American bank.

More than 22 countries small and large have applied to join the group – that will be competing with the G7 and G20 for global influence. The first announcement was about this. The other top agenda item of the Johannesburg meeting of August 22-24 is how to reduce the importance of the dollar as a global reserve currency. The economies of the BRICS are already larger than those of the G7 combined. But an attractive new currency can’t be created overnight, and the demise of the dollar “extravagant privilege” won’t disappear anytime soon. However, bilateral agreements for more trade involving national currencies instead of the dollar are growing fast. The incentives to do so have risen because of the dollar’s all-time strength, and the rise in the dollar-related interest rate. Abusing the dollar’s dominance to impose US unilaterally-led sanctions will speed up its ultimate demise. The BRICS group risks becoming China’s bloc, or worse, the “illiberal bloc” – that competes against the US and EU, and against the world’s democracies. But there are many forces against such clear-cut realignments; India, Argentina, or Brazil do not wish to embrace China’s dictatorial populism. Others – such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Turkey, or Egypt – seek a positioning between the two large blocs. In fact, for all these countries, the benefit of belonging to the rising group is to protect themselves from undue pressure to join the US or the China camps, by formalizing their non-alignment into a collective rock to which they can all dock their boat. Most of these countries have already refused to take sides on the Ukraine war, using the “not my war” argument. An enlargement would strengthen non-alignment, even though China is also militating for a larger group, hoping to increase the size of its global supporters. But this comes at a time when the ambition its belt-and-road initiative and its financial involvement abroad have been severely reduced. Its developing economic recession will diminish its global influence further. China retains a mighty global influence, but it is unlikely that its economic or political systems will become attractive enough to allow it to build a large global fan-club of countries willing to offend the US and EU for its sake. In fact, the mere creation of a non-aligned bloc is a victory for China, as it moves the world away from a unilateral US- dominance. As the group become more representative of a “Global South” it will find plenty of causes that unite - the question is what can be done collectively, besides affirming non-alignment. There is a pool of grievances. There is a long list of initiatives that meet joint interests. This includes the non-availability of Covid vaccines when they were urgently needed (“is an African life cheaper than one in rich countries?”), to the rise of food and fuel prices following the Ukraine war, to the current rise of global interest rates to deal with the G7 overspending during Covid, to the failing of the global safety net to help developing countries avoid falling into a developmental and a debt crisis. The rising effect of global warming, to which they have barely contributed, but whose negative impact hits mainly their populations, is turning unhappiness into anger. There are two other sources of rising discontent. De-globalization is making the project of income convergence through an export-led model less feasible. In addition, fast technological change is further eating into the potential comparative advantage of poor countries – their labor force – by pushing for robotization and digitalization, threatening countries with low levels of skills to fall behind hopelessly. This suggests several possible agendas for an enlarged Global South group: fighting together to reform the global development finance system; to work at increasing South-South trade; to bargain their entry into a global deal on the environment for concessions on adaptation finance, the transitory use of gas, support in developing green energy, and faster transfers of technology. Whether the group can hold the line to negotiate with one voice is an open question. Federating interests and voice could start continentally. Africa is poised to have a louder global voice, as the African Union becomes better organized, and a permanent seat on the G20 is already on the horizon. ASEAN has been a rather organized group for a while now, which has been reinforced as Indonesia headed the G20 more recently. Latin America and the Caribbean had a head start with the development of the Bridgetown Initiative, which includes many of the issues and joint causes listed above. By coming together, these disparate countries will also discover that there are many economic forces that divide – even when putting the governance-model and geo-political divisions aside. In particular, the interests of the middle- and low-income countries are not aligned on most of the core issues already mentioned. For example, the issue of how to allocate the additional concessional finance provided by the enlargement of the multilateral development banks - to support poverty reduction in the LICs, or the green agenda in the MICs, is already deeply divisive. Undoubtedly, the August 2023 BRICS meeting will be remembered for being that of its expansion. This will raise expectations for the emergence of an organized group of countries to represent the interests of the Global South on the global stage. In the 1960s, the Soviet Union managed to ultimately kill the non-aligned movement by hugging it too closely. Whether an enlargement of the BRICS will manage to avoid a deadly kiss from China, and its internal division – to make the Global South an effective counterpart to the established blocs of the new multipolar world remains to be seen. The Arabs will be represented in Johannesburg by the ambassadors of MBS and MBZ. Their goal is to be at an equal distance of all blocs to be in the best position to continue to sell oil as long as possible, even as the world decarbonizes. In contrast, the preparatory meeting of the non-aligned was organized by Nasser in Cairo in 1961 – the main topic was to support the decolonization movement. The contrast alone is a sign of how the times are changing… Yeghia Tashjian Between June 14-17, 2023 I had the opportunity to participate in a program organized by the “Friends for Leadership” to attend the Saint Petersburg International Economic Forum. Thousands of delegates mostly from Latin America, Africa, and Asia attended the forum alongside heads of state, diplomats, and businessmen. Interestingly, the UAE had the “special guest” status and anyone could feel its cultural, economic, and political presence in the forum. Delegates were anxious to be informed of the details of the new agreements signed between Russia and other countries, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin’s remarks and attend dozens of sessions and panels related to the BRICS, Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), International North-South Transport Corridor, and North-South trade. Personally, I had the opportunity to closely identify Russia’s post-Ukraine war foreign policy priorities, its geo-economic interests in the Middle East, and the challenges of the emerging multipolar world system.

The Middle East within the Context of the INSTC What is the INSTC and why is it important for Moscow’s geo-economic interests in the Middle East? The International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), is a 7200 km model of ship network, rail, and road project that was initiated in 2000 by Russia, Iran, and India to facilitate trade between India and Russia, and Europe. This transport corridor aims to reduce the delivery time of cargo from India to Russia and Northern Europe to the Persian Gulf and beyond. Compared with the sea route via the Suez Canal, this route’s distance shrinks by more than half, which brings the term and cost of transportation down. If the present delivery time on this route is over six weeks, it is expected to decrease to 3 weeks through this corridor. Hence, INSTC not only saves time but also decreases cost. The project is planned to have three routes:

Hence, we can see that the Persian Gulf plays a crucial role as an import-export transit hub for Russia connecting it to Asian markets or even the Eastern Mediterranean. As Iran is also looking forward to constructing a railway connecting the Persian Gulf to the Syrian port of Tartous aiming to bypass US sanctions, though for now, this seems a difficult project to be implemented due to a lack of foreign direct investment and the political situation in Syria. During the business dialogue session between the UAE and Russia, where later Vladimir Putin and UAE's President Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan had a meeting at the forum, important matters were discussed. First, Russia and Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) proposed to the UAE the signing of the Free Economic Zone and Trade Agreements, negotiations are underway and we may witness an agreement by the end of the year. Trade turnover between the two countries has doubled over the past year and now amounts to USD 10 billion. During the bilateral meetings, Russia’s Industry and Trade Minister Denis Manturov said “we are constantly expanding the range of areas in which we build joint work. We are implementing several industrial cooperation projects, and initiatives in the fields of transport and services, energy, and food security. We have started an active negotiation process on a free trade agreement between the UAE and the states of the Eurasian Economic Union.” This is another indication that Russia is moving toward the South and values the Persian Gulf as an import-export hub for the North-South Transport corridor. On the other hand, the UAE President said he has been under Western pressure. Within this context, Russia also is in negotiations with Egypt to sign a free economic zone between EAEU and Egypt. Of course, these agreements would have clear implications for our region, whereby:

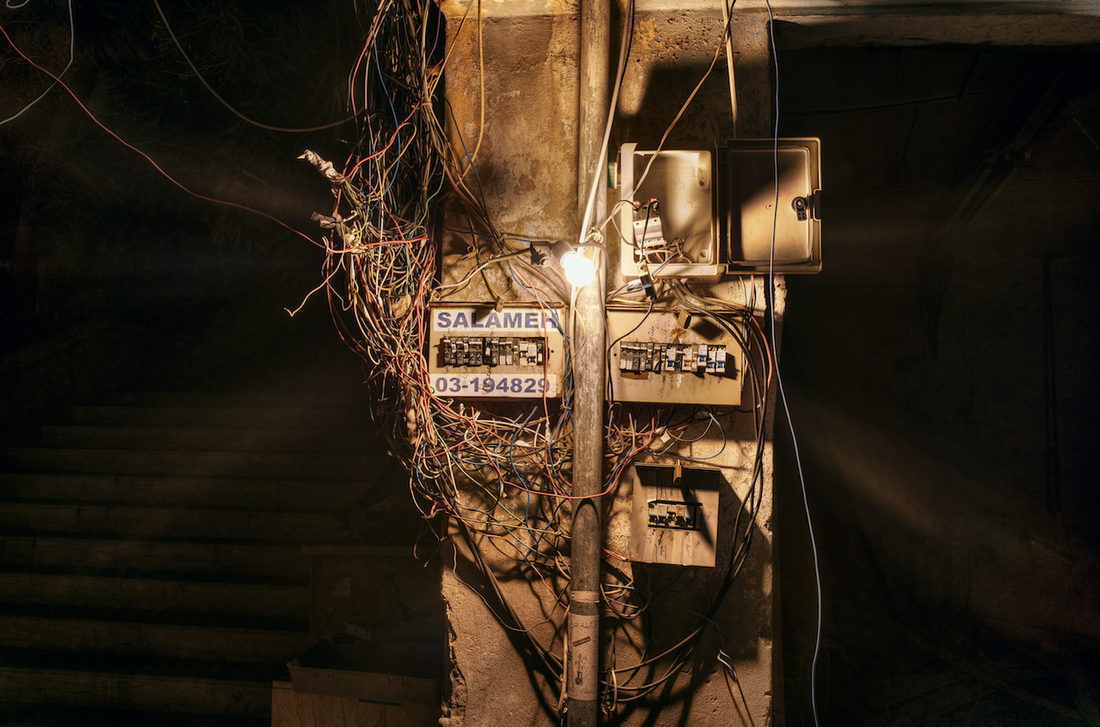

Why is Russia interested in Sea Ports? This was another interesting question that I started asking and discussing with Russian experts in the forum. In one of the panels that I attended “Russian Fleet for New Maritime Transport Corridors” the panelists argued that in terms of trade, a new “iron curtain” is being built with the West, and while trade with Europe is facilitated by a dense network of roads, railways, and pipelines, routes connecting Russia to Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, and many Asian countries are made via the sea. It is the growing importance of sea-based trade that creates the material basis for Russia’s re-emergence as a maritime power, in addition to Moscow’s interest in naval power. Interestingly, Russia also plans to exploit the Northern Sea Route by transforming it into a strategically important cargo route linking Asia and the Pacific to Europe. Moreover, grain production is now crucial for Moscow. It is within this context that we have to analyze the importance of the Tartous Port for Russia as a Russian grain storage hub in the future for Middle Eastern and African countries. Because grain exports are growing so rapidly, existing export terminals are undergoing modernization and new capacity is being added. The Black Sea’s role as the gateway for food export markets across the world means that the ports of the East Med as a transit hub will only grow in importance. Hence, as Russia’s maritime economic interests grow, and with the importance of the sea to Russia’s maritime strategy, so does the need to guarantee sea communication lines and bolster Russia’s military presence around key seaports. Multipolarity, De-dollarization, and the Future of BRICS Many panels and bilateral talks during the forum were dedicated to multipolarity, de-dollarization and the future of BRICS. All panelists agreed that we are moving towards a multipolar world order where no single hegemon will dictate its terms to others. However, there were some differences of opinion when it comes to the structure of this system to different players. BRICS (Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa) is becoming a rising de-dollarization coalition, whereby the group is developing multiple de-dollarization initiatives to reduce currency risks and bypass US sanctions. However, it is not realistic, at least for now, to argue that the group will initiate a common currency replacing the USD. During the panel debates, many opposing ideas from different representatives of member states were presented in this regard. All member states aimed for de-dollarization, but nobody was in favor of a common currency to replace it, even though their aim is to establish a polycentric global monetary system by promoting the internationalization of the currencies of its member states. A further indication of booming trade in de-dollarization is shown through BRICS countries’ national currencies, which have progressively gained more market share in the US dollar-based global currency system. There were also diverging ideas between China and India. While the Chinese speakers showed “calmness,” the Indian speakers were always “defensive,” raising concerns about the trade deficit with Russia and complaining that India should not be viewed as a “junior partner” and should be “treated equally.” As one of the Indian diplomats said, “we need Russia to consider us a full-fledged power with a sovereign economy.” It was made quite clear that the BRICS no longer see themselves as an economic force, but also as a powerful geopolitical actor, and the organization is looking to add new partners and a new format of cooperation. Uncertain Future for an Uncertain Region The post-Ukraine conflict developments have shown us that the global order is heading toward an uncertain future. Unipolarity is being replaced by a new order, but it is still uncertain whether it will be replaced by multipolarity or if we are just living in a transitional period to enter into a new bipolar political and economic system. The difference between the cold war bipolar and the possible future bipolar system is that there is a lack of ideological commitment, and under each pole, there are many actors that may move from one pole to the other based on their national interests. Will this trigger instability or will it balance the system? The Ukraine war has pushed Russia to reprioritize its objectives in the Global South, mainly the Middle East. While the region is experiencing a cautious “normalization” period, trade and interconnectivity may shape its future political order, though uncertainty is still the dominant factor in the Middle East. As new rising economic actors in the Persian Gulf are monitoring global events and acting based on their national interests, the Middle East will once again become the center of gravity of global geopolitical and geo-economic developments. Ishac Diwan Lebanon is in a deep hole. Not only is its financial sector badly broken, but so is the state and indeed, its economic model. The country is now much poorer and more unequal. We are stuck in a poverty trap, and it will take generations, or a miracle, before the proverbial phoenix manages yet another rebirth.